Say a prayer as you drive by Calvary Cemetery in the messy triangular intersections of Ninth Avenue and Twenty-Fifth Street and Lombardy Drive in Port Arthur. Buried there in an unmarked grave alongside hundreds of other Catholic folks is Delphine Huntington Williams (1860-1930).

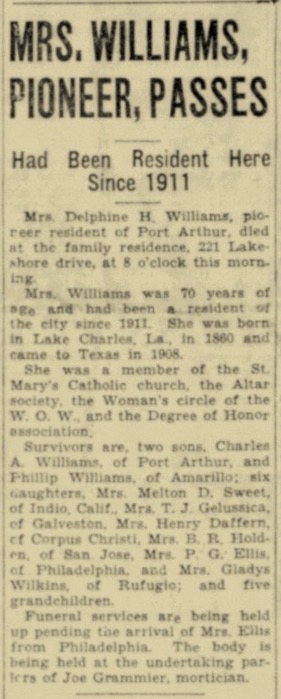

Delphine died on August 7, 1930. An obituary on the front page of the Port Arthur News celebrated her as a pioneer citizen of the city, a mother of eight children, and a member of the altar society of St Mary’s Catholic Church. Fifteen years later, the morning after the US detonated an atomic bomb over Hiroshima, the Port Arthur News carried a column headed “15 Years Ago Today…” It said: “Mrs. Delphine H. Williams, pioneer Port Arthur resident, died at her home, 221 Lakeshore drive.”

She was indeed a pioneer Port Arthur resident, and I’m sure she was a faithful mother and a member of the altar society at St Mary’s. But Delphine Williams carried an important secret to the grave with her. Few could have known.

It takes a little explaining. Delphine had been born in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana, in the year before the Civil War began, 1860. Her father, Ambrose P. Huntington, a native of New York state, had been born in 1823. He had come to Louisiana and settled in Calcasieu ten or fifteen years before the war, He joined the Confederate army in 1860: yes, it seems odd, but he joined the Confederate Army. He was captured at the battle of Missionary Ridge in Tennessee in 1863, spent a year or so in a Union prison in Illinois, swore out an oath of allegiance to the United States, and returned to Lake Charles at the end of the war.

Ambrose Huntington fathered Delphine and Delphine’s sister Ellen by a woman who had the French name Louison Bonin. Louison—with some justice—took up the surname Huntington after she bore children by him, even though there’s no evidence that she and Ambrose were married and no evidence that Ambrose took any responsibility for the two daughters he fathered by Louison.

Louison’s daughter Delphine Huntington married Mississippi native John Robert (J.R.) Williams in Houston in 1881. They would eventually have seven daughters and two sons. Most of their children were born in Calcasieu Parish, but by 1900 they lived in Leesville in Vernon Parish, Louisiana, on the border with East Texas. In Leesville, J.R. worked in the lumber industry, harvesting pine trees sent down the Calcasieu River to Lake Charles where they were processed and shipped out.

By 1908 Delphine and J.R. had moved to Beaumont, Texas, where they lived in a boarding house on Cypress Street on the banks of the Neches River from which pine logs harvested in East Texas were fetched out of the water, processed, and shipped away. In the 1920 census, Delphine was shown as the proprietor of a boarding house in Port Arthur with 21 boarders in addition to two of her daughters, but J.R. was no longer with her. He was shown as a resident of the Texas State Hospital in Austin in that year, and he died in 1921. When Delphine died nine years later in 1930, she was proprietor of a smaller boarding house on Lakefront Drive on the ship channel in Port Arthur where she lived with her son Grover Charles Williams, a ship’s cook.

Here’s the secret that Delphine and her children knew and the public at large did not know: Delphine’s mother Louison had also been known as Kishyúts in the old native language of southeastern Texas and southwestern Louisiana, a language that Delphine and her sister Ellen had learned from their mother Louison/Kishyúts. Delphine may have looked like everyone else. She may have talked in public like everyone else. But unknown to almost everyone around her and certainly unknown to the Port Arthur News, she was one of the native people of southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas, the Atakapa people.

How do we know? In 1885, Dr Albert Samuel Gatschet of the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology traveled to Lake Charles where he interviewed Delphine’s mother Kishyúts (Louison Bonin/Huntington) and her aunt Tóttoksh (Delia Moss) who also spoke the native Yukhíti (Atakapa) language of southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas. A later Smithsonian investigator, John R. Swanton, described “Ellen Sclovon or Esclovon” and “Delphine Williams, wife of J. R. Williams, Beaumont, Tex.” as surviving speakers of the old language in 1908.

Delphine Williams’s 1930 death certificate lists her father’s name as Daniel P. Huntington (I believe it should be Ambrose Huntington) and shows her own middle initial as “H” for Huntington. It shows her mother’s maiden name as “May Lou Bonney,” a corruption of the common Louisiana French name Bonin typical of many Atakapa descendants: her mother was Louison née Bonin Huntington whose Atakapa name was Kishyúts.

The native people of southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas had called themselves Yukhíti for centuries. Other native people called them Atakapa (pronounced like attack-a-paw) which meant “people eaters.” Despite its demeaning connotations, the name “Atakapa” became and remains the most common name for the Yukhíti people, even among themselves today.

We can’t identify many of the historic native people of southeastern Texas by name, but we can name Delphine Williams, the daughter of Kishyúts (Louison), the daughter of Kishmók (also called Ponponne), one of the five daughters of the Atakapa Chief Shukuhúy. Delphine knew deeply the native language that had been spoken in this region for centuries. I ask you to remember Delphine:

LUX PERPETUA LUCEAT DELPHINAE POPULOQUE EIUS +

May light perpetual shine on Delphine and her people.

Sources:

John Reed Swanton’s Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Adjacent Coast of the Gulf of Mexico (Bureau of American Ethnology bulletin 43; Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1911, pp. 362-363 identified “Delphine Williams, wife of J. R. Williams, Beaumont, Tex.” as one of the nine surviving speakers of the Yukhíti (Atakapa) language in 1908 and the only one mentioned in his account as living in Texas in that year. Swanton’s information was based on visits to the remaining speakers of the Yukhíti (Atakapa) language in 1907 and 1908. An obituary for Delphine Williams was printed in the Port Arthur News for August 8, 1930, and the notice about her 15 years later appeared in the Port Arthur News for Tuesday, August 7, 1945, page 4. Other information about Delphine Williams relies on census and other public documents.